I love science. Not just in the facebooky “I fucking looooove science, look at this crazy fangly fish!” way (although I totally do that, too). I love science the way my born-again friends love Jesus. I believe in science, I have faith in its reality and ability to enrich our lives, and I am dedicated to sharing it with the world. So naturally, I’ve watched every episode of Cosmos. There’s one segment in particular that has stood out for me, especially since starting my M.Ed, and it’s this one:

“Keep your eye on the man. Not the dog.”

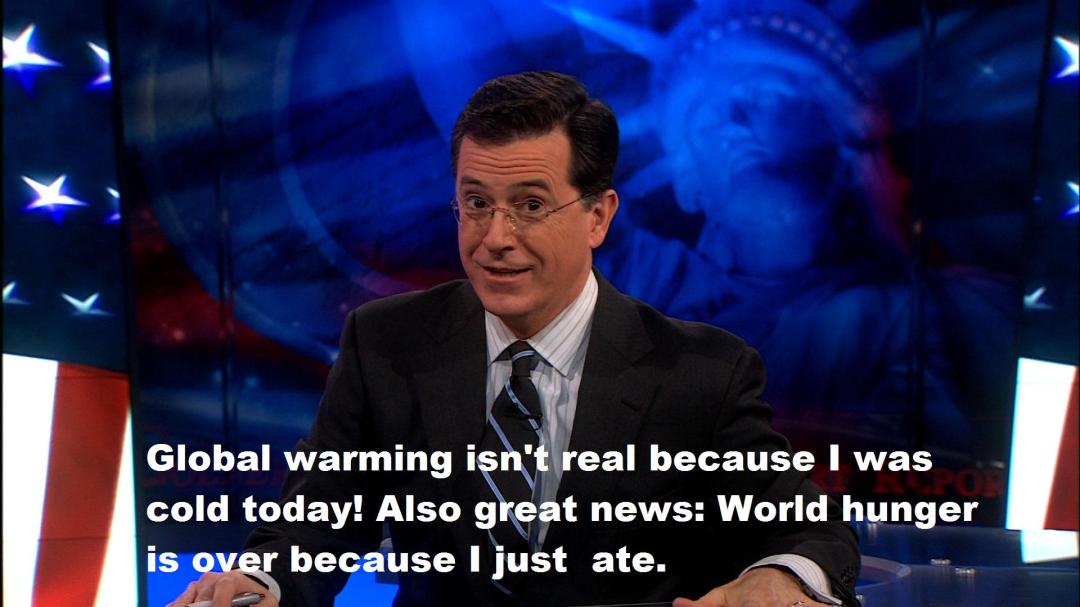

This doesn’t just apply to climate science. Our tendency to “watch the dog” is a major impediment to public understanding of a wide number of statistically-proven science concepts: the safety of vaccines and their inability to cause Autism, the relative risks of pregnancy vs. abortion (spoiler alert: abortions are safer), the decreasing national crime rate, and so on.

If we want to watch the man, and not the dog, we have to remember that any single piece of data — a single weather report, a single violent crime, etc. — gives us a very limited amount of information about what happened in a single place at a single moment in time. A single datum is essentially useless unless considered along with a number of other data points. The more data points you collect, the more information you have, and the more likely it is that the trend you identify (such as a warming planet or a decreasing number of violent crimes) is really trending.

This is true no matter what data you are collecting. No matter what, we cannot make scientifically accurate generalizations about a single data point. Just because one person got a bad rash after a vaccine doesn’t mean all vaccines cause rashes in all patients; just because my daughter had a potty accident today doesn’t mean she has lost all control of her bladder.

And this is exactly the problem with how we use standardized tests.

State-mandated, standardized tests are designed to give educators information on how well students, as a group, can answer questions about the curriculum they’ve learned. That “as a group” is really important. An individual student’s score on that one state-mandated test doesn’t really help anyone, because it is just one little data point — the dog, in Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s metaphor. Any number of factors, like a poor night’s sleep, a cold coming on, problems with the computer testing program, a lot of lucky guesses, and so on, could have influenced that individual score. But if you gather, say, 1000 data points, the odds are good that the average test scores accurately reflect the average proficiency of that group of students.

This is very useful information for a superintendent in charge of a school district serving 15,000 students. It’s useful for the consortium of professionals who determine state educational standards. They can see how students are doing, on average, and work with school administrators to set goals for improving or maintaining students’ achievement in core subjects. When you work with a large collection of data, like the superintendent or the policy maker, you are “watching the man,” and thus able to make a limited number of very important policy decisions. This is good, and useful!

But that information is next to meaningless for a kid, a parent, or even a teacher.

And yet.

- We use standardized test scores to judge teacher effectiveness- even for teachers whose subjects aren’t tested (like gym teachers and speech-language pathologists).

- My third graders were told that their test scores would account for one-third of their fourth quarter grade.

- Parents receive score reports that tell them that, based on this test score, their child may not be “on track” for college or careers.

Testing companies and state-level policy makers are encouraging principals, teachers, parents, and children to “watch the dog” — to focus on these single points of data as though they are key to determining whether our students are learning. The average self-contained public school classroom in Tennessee has 18 students. I couldn’t even pass my thesis proposal without at least 20 participants to study, because if you have less than that, you can’t accurately judge statistical significance. But we can fire teachers over statistically insignificant data?

That is unacceptable.

Luckily, the solution is actually quite simple. We just stop using test scores to judge individual students and teachers, or for punishing schools.

Those of us in education already know that this would be a valuable policy change because it’s what we do every single day. I can’t diagnose a student as having a learning disability in reading based on a single test score — I have to give multiple tests, gather samples of their work over time, talk to their teachers and parents, and work with a team to decide whether that student has a disability. When a fifth grade teacher sees that a student of hers bombed the last math quiz after months of good grades, she doesn’t decide that he’s actually bad at math and needs a tutor — she tries to see what might have influenced his performance that day, talks to him about the quiz, and gives him a chance to try again. That’s because as teachers, we have to watch the man. Otherwise, we risk making terrible and unnecessary judgments that leave lasting, negative impacts on our students.

Schools and districts will certainly benefit from seeing standardized test scores, but the practice of financially punishing schools based on low scores is just as misguided as using them to judge teacher effectiveness. And luckily, the reasoning behind that doesn’t even require knowledge of statistics, because it turns out that nobody has been trying to lower their students’ test scores.

And there’s one other thing we can do — and luckily, we can do it without waiting around for the Department of Education.

Start teaching students how to understand basic statistics and data science.

When all of us have this knowledge, we can understand scientific reporting, use data appropriately, and make better choices for our kids, our environment, and the public. Right now, too many educated people refuse to believe in science unless it confirms their biases. That’s what Trump does. That’s what Rex Tillerson does. Oil companies, cigarette manufacturers, fuckin’ Jenny McCarthy, they’re all taking advantage of public ignorance and profiting off of it. We’re putting our schools, public health, civil rights, and the environment in danger because we believe it when they say “but look at the dog!”

In this new Trump era, it is more important than ever that we equip ourselves (and our children!) with the skills to analyze data and think critically. We can help them protect their futures by teaching them to “watch the man.”

Let’s get free, y’all!

Are you a Neil DeGrasse Tyson fan? Has your knowledge of science and testing changed your perspectives as a teacher? How do you feel about the way we use test scores in school, or how climate science has been reported? I wanna know! Share in the comments!